Javascript: This Keyword and Object Oriented Programming

Resources

This

The this keyword is the foundation of OOP (Object Oriented Programming) in Javascript.What is this?

- A reserved keyword in Javascript

- Usually determined by how a function is called (execution context)

- Can be determined using four rules

- global

- object/implicit

- explicit

- new

In short, the value of this is determined by the context, like the scope of a variable. Let’s start first with understanding when the context of this is global.

Global

When this is not inside of an object, implicitly or explicitly determined it become a global variable, and when that happens this refers to the window. A simplified way to refer the window is that it is the screen itself, and everything inside of it. The DOM document is inside of the window.

Here is an example of when this refers to the window, as it is not defined by anything else.

console.log(this) // window

function whatIsThis(){

return this

}

function variablesInThis(){

this.person = 'Nick'

}

console.log(person); // Nick

whatIsThis(); // window

As we can see in this example, even though we have declared this.person to be Nick inside of a function, if we call person outside of the scope of that function we still get Nick as a value. It is now available anywhere in the window. In fact all global variables are attached to the window object.

“use strict”

There was a feature added is ES5 that can help to prevent us from accidentally declaring global variables. For example in the code above we made person a global variable, which is a horrible practice. If we add "use strict" to the top of our document we will be prevented from doing this with a typeError.

Object/Implicit

This is the most common method of using this. In this example we are using this inside of a declared object (person).

let person = {

firstName: 'Nick',

sayHi: function(){

return 'Hello ' + this.firstName;

},

checkHumanity: function(){

return this === person;

}

}

person.sayHi() // "Hello Nick"

person.checkHumanity() // true

Because this is within the context of the person object, this === person. So in this case the checkHumanity function would evaluate to true.

Call

Call, Apply and Bind are methods that can only be used on functions that allow us to explicitly set the value of this. Again, these cannot be used on strings or numbers or boolean.

The parameters of the call method are (thisArg, a, b, c, ... ) where thisArg is what we would like the value of this to be, followed by whatever other parameters we would like to include.

When the call method is applied the function is invoked immediately.

Let us take the following example.

let person = {

firstName: 'Nick',

noise: 'why are you recording me?',

checkHumanity: function(){

return this === person;

},

makeNoise: function(){

return this.noise;

},

elephant: {

firstName: 'Daisy',

noise: 'trumpeting',

checkHumanity: function(){

return this === person;

},

makeNoise: function(){

return this.noise;

}

}

}

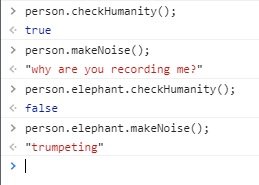

person.checkHumanity();

person.makeNoise();

person.elephant.checkHumanity();

person.elephant.makeNoise();

Within the elephant object this is referring to elephant, and therefore we get false and trumpeting for the elephant functions. However if we change those functions by applying the call method like this

person.elephant.checkHumanity.call(person);

person.elephant.makeNoise.call(person);

We have replaced the value of this in the elephant object methods with the value of this in the person object.

Practical Uses

One of the practical uses for the call method would be to avoid duplication of code. Take for example the following two objects.

let person = {

firstName: 'Nick',

noise: 'why are you recording me?',

checkHumanity: function(){

return this === person;

},

makeNoise: function(){

return this.noise;

},

}

let elephant = {

firstName: 'Daisy',

noise: 'trumpeting',

checkHumanity: function(){

return this === person;

},

makeNoise: function(){

return this.noise;

}

}

We obviously have repeated the checkHumanity and makeNoise functions. We can refactor this to remove duplication and also improve organization.

let animalFunctions = {

checkHumanity: function(){

return this === person;

},

makeNoise: function(){

return this.noise;

},

}

let person = {

firstName: 'Nick',

noise: 'why are you recording me?',

}

let elephant = {

firstName: 'Daisy',

noise: 'trumpeting',

}

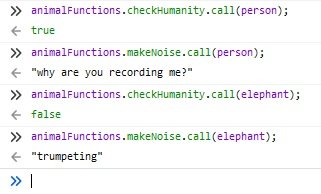

We move all the functions to a new object called animalFunctions and the animals to their own objects with just their properties. Then we can use call combined with this in the functions and we get these nice verbose function strings.

animalFunctions.checkHumanity.call(person);

animalFunctions.makeNoise.call(person);

animalFunctions.checkHumanity.call(elephant);

animalFunctions.makeNoise.call(elephant);

Now that is useful!

Apply

The parameters of the apply method are (thisArg, [a, b, c, ...]) where thisArg is what we would like the value of this to be, followed by whatever other parameters we would like to include inside of an array. apply only accepts two parameters, but one of them may be an array.

When the apply method is applied the function is invoked immediately.

Ok so why is this useful? Well many times we may want to pass in an array as an argument, and this makes that easy to do. For example an array of numbers that we would like to do some math on.

Bind

bind is similar to call, but instead of executing the function immediately, bind returns a function definition.

The parameters of bind are (thisArg, a, b, c, ...).

The parameters work like call, but bind returns a function with the context of this bound already.

let animalFunctions = {

poundsToKilograms: function(lbs){

return this.firstName + ' weighs ' + (lbs/2.205) + ' kilograms';

}

}

let person = {

firstName: 'Nick',

}

let elephant = {

firstName: 'Daisy',

}

let convertedWeightString = animalFunctions.poundsToKilograms.bind(elephant, 2500);

convertedWeightString();

Asynchronous

Consider the following function:

let cow = {

weight: '1000 lbs',

name: 'daisy',

age: '10 years',

listFacts: function(){

setTimeout(function(){

console.log(this.name + " is " + this.age + " old and weighs " + this.weight);

}, 5000);

}

}

cow.listFacts();

When we run this we expect to get a string back listing name age and weight of the cow. At first glance it appears that this is clearly referring to cow because it is inside of that object. However when we run this we get the following.

What is happening here is that the setTimeout method is an asynchronous function and is therefore running at a different time than the object. Specifically five seconds in the future, at which point the runtime environment will no longer be tracking this keyword. This is where bind is necessary. Let us add bind to this function so that the function passes the value of this into the future.

let cow = {

weight: '1000 lbs',

name: 'daisy',

age: '10 years',

listFacts: function(){

setTimeout(function(){

console.log(this.name + " is " + this.age + " old and weighs " + this.weight);

}.bind(this), 5000);

}

}

cow.listFacts();

New

We can set the context of the keyword this using the new keyword. That sets us up for OOP.

function Car(make, model){

this.make = make;

this.model = model;

}

var mysteryMobile = new Car('Chevrolet', 'Astrovan');

console.log(mysteryMobile.make);

console.log(mysteryMobile.model);

Here are the things that the new keyword is actually doing behind the scenes.

- Creates an object out of thin air

- Assigns the value of ‘this’ to be that object

- Adds ‘return this’ to the end of the function

- Creates a link (which we can access as

__proto__(dunderproto) between the object created and the prototype property of the constructor function

Object Oriented Programming

Object oriented programming is a programming model based around the creation of objects using blueprints for those objects. The blueprints are typically referred to as classes, and the objects that are created using those classes are called instances.

This is very similar to the concept of Schemas in Mongoose. We create a schema and then use that schema to create documents in the Mongo DB. Here we use our classes to create instances.

One of the goals in OOP is to make classes abstract and modular so that they can be shared across many parts of an application.

Many programming languages like Python and Ruby have built in support for classes. Javascript does not, but we can mimic the behavior of those languages with functions and objects.

Object Creation

Lets take a quick look at a problem that OOP solves for us. Let us say that we want to make a collection of cars. We could do the following.

let car1 = {

make: 'Subaru',

model: 'Forrester',

seats: 4,

engine: '2-liter V6',

miles: 100,250

}

let car2 = {

make: 'Chevrolet',

model: 'Suburban',

seats: 7,

engine: '4-liter V8',

miles: 85000

}

let car3 = {

make: 'Toyata',

model: 'Prius',

seats: 5,

engine: '2-Liter Hybrid',

miles: 55,000

}

let car4 = {

make: 'Mitsubishi',

model: 'Eclipse',

seats: 4,

engine: '2-liter V6',

miles: 120000

}

// forever and ever so many cars

This is wildly repetitive, especially once we start making hundreds of these objects. Let’s instead use classes and instances.

Constructor Function

First let’s make the class for Car.

function Car(make,model,seats,engine,miles){

this.make = make;

this.model = model;

this.seats = seats;

this.engine = engine;

this.miles = miles;

}

Note that we purposefully capitalized Car. Typically functions are written with camelCase. However when we make classes it is conventional to capitalize them.

Note that as of 2015 there is a new method to write classes and constructors. JavaScript classes, introduced in ECMAScript 2015, are primarily syntactical sugar over JavaScript’s existing prototype-based inheritance. The class syntax does not introduce a new object-oriented inheritance model to JavaScript. EX:

class Motorcycles {

constructor(make, model, year) {

this.make = make;

this.model = model;

this.year = year;

this.numWheels = 2;

}

}

Visual Studio will even prompt you to reformat to these when it detects a constructor class.

Instances

Now using the new keyword we can create new instances using this constructor.

let car1 = new Car('Subaru', 'Forrester', 4, '2-liter V6', 100,250);

car1.make // Subaru

car1.model // Forrester

Multiple Constructors

It is possible to borrow parts of one class inside of another class to avoid duplication even inside of classes. Let’s take a look at an example.

function Car(make, model, year){

this.make = make;

this.model = model;

this.year = year;

// we can also make preset values

this.numWheels = 4;

}

function Motorcycles(make, model, year){

this.make = make;

this.model = model;

this.year = year;

this.numWheels= 2;

}

We have a lot of repetition between these two classes. We can use call or apply to take portions of the Car constructor.

function Car(make, model, year){

this.make = make;

this.model = model;

this.year = year;

// we can also make preset values

this.numWheels = 4;

}

function Motorcycles(make, model, year){

// using call

Car.call(this, make, model, year)

this.numWheels= 2;

}

and we can then refactor this down even further with arguments

function Motorcycles(make, model, year){

// using call

Car.call(this, arguments)

this.numWheels= 2;

}

Prototype

There is a great article on this here:

Medium: Javascript Prototype and Prototype Chain Explained

What do prototypes do? First let us do a recap of what the new keyword is doing when we use it.

- Creates an object out of thin air

- Assigns the value of ‘this’ to be that object

- Adds ‘return this’ to the end of the function

- Creates a link (which we can access as

__proto__(dunderproto) between the object created and the prototype property of the constructor function

// this is a constructor function

// constructor functions have a property called prototype

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

// this is an object created from the Person Constructor

let elie = new Person ('Elie');

let nick = new Person ('Nick');

// since we used the new keyword, we have established

// a link between the object and the prototype property

// we can access that using __proto__

elie.__proto__ === Person.prototype; // true

nick.__proto__ === Person.prototype; // true

// the Person.prototype object also has a property

// called constructor which points back to the function

Person.prototype.constructor === Person; // true

So in a nutshell the prototype is the link between our constructor and our objects. It allows us to apply properties to all of our objects at once and reference each other.

// this is a constructor function

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

// this is an object created from the Person Constructor

let elie = new Person ('Elie');

let nick = new Person ('Nick');

Person.prototype.isHuman = true;

elie.isHuman; // true

nick.isHuman; // true

And now these seemingly unrelated objects have something in common. This is the way that Javascript finds methods and properties on objects. This process is called the prototype chain.

Adding Methods to Prototype

Let us take the following example

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

this.sayHi = function () {

return "Hi " + this.name;

};

}

}

nick = new Person('Nick');

nick.sayHi(); // Hi Nick

This code works but it is inefficient. Every time we make an object using the new keyword we have to redefine this function, even though it is the same for everyone. If we put it on the prototype we can avoid this.

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

Person.prototype.sayHi = function(){

return 'Hi ' + this.name;

}

nick = new Person('Nick');

nick.sayHi(); // Hi Nick

This is a best practice where are only defining the function once.

Comments

Recent Work

Basalt

basalt.softwareFree desktop AI Chat client, designed for developers and businesses. Unlocks advanced model settings only available in the API. Includes quality of life features like custom syntax highlighting.

BidBear

bidbear.ioBidbear is a report automation tool. It downloads Amazon Seller and Advertising reports, daily, to a private database. It then merges and formats the data into beautiful, on demand, exportable performance reports.